ARTICLE - FAIRIES, CHILDHOOD

A SIMPLE FAIRY STORY

Once upon a time there were two brothers who lived on the edge of the woods. Both were born with a hideous humps on their back.

One day, one of the brothers set out to walk into the village. While passing the fairy fort he heard music. The fairies came out and invited him in. They played for him the most magical and beautiful music he had ever heard, they fed him delicious food, played games with him and if that wasn’t enough, they even took the lump from his back.

Delighted, he returned home to tell his brother of his great adventure and good luck.

The next day, his brother set out and heard music while passing the fairy fort. The fairies invited him in. He was ecstatic thinking he would have a similar experience to his brother and he waited joyfully in anticipation of magical music, delicious food. To think he too might no longer have a lump on his back.

So, he was horrified when the fairies were cruel to him, whipped him. Not only did they not take away his lump - the gave him the lump from his brother's back.

The poor man went home beaten, disappointed and carrying two humps on his back!

So, is there a moral to this story? I would say - no. Nor do we find a moral in most fairy stories. An interesting thing about fairylore is that it's likely to interweave nicely with whatever it is you believe in the first place. The one thing it clearly does is reflect life. One day you walk down the street and have a great day. The next, who knows?

Is there harm in needing time or mechanism outside of ourselves to help us accept life. Why is it that a man can leave his home one morning and stumble upon a miracle; and on another day, his brother following a similar path returns at evening with twice as many troubles as he left with that morning?

For whatever reason, you walk down the next day and all hell breaks loose! These types of stories don’t explain the “why.” They simply make it clear that “life happens” and while we wait for understanding, acceptance and the bigger hand to comfort, these reflections of humanity can serve a wise and lovely purpose for our common frailties as human beings.

CHILD CARE AND FAIRY LORE

As you might expect, a great deal of fairy lore revolves around children. What’s surprising is the social utilizing of fairy lore around child care and safety. A simple folkloric strain around fairy lore was that if you didn’t value your children, there was something out there that would happily take over the job for you. This might sound strange to us in a modern world but in a pre-internet, pre-psychology and media-free world, how was a mother (and many entered motherhood at a very young age) to be cajoled and prove capable of care in societies where infant mortality rates were high and family sizes were generally large?

I never cease to be amazed by the wisdom and simplicity of some of these tales and traditions. The superstition ran that fairies loved beautiful little children and that if they were not watched, or if the house was not keep free of clutter and essentially clean, the fairies might well be drawn in to “take” the child. It would be a mistake to view our ancestors as fools. However, the overriding sense that children were precious and to be minded is the main theme here.

Since mothers tend toward worry over their young children, the world of fairy didn’t just offer a projection for those worries; guarding against the fairies gave a mother a series of tasks to prevent any harm coming to her child. They were imminently practical measures around watchfulness and maintenance.

To look at the nature of fairies is to look at a wide spectrum of human nature but overall their quality was childlike, but children have an amoral quality and this is what made the world of fairy a precarious proposition and a place that could be visited but should never become a habit or habitation for the average mortal…

CHILD LOSS, CHANGELINGS AND FAIRY LORE

So where did this idea of the fairies taking children come from? Like so much of fairy lore, it sounds like superstition and perhaps even ignorance. But any time you scratch a folkloric tradition or strain of thinking, there’s probably something interesting there…

The myth of the Changeling did serve a societal purpose. The stories of a changeling revolve around the idea of a mother’s child being “taken” by the fairies and a sickly fairy child being left in his/her place. The exchanged “fairy” child would generally get sicker and sicker and die. It’s little wonder that we look at these stories, shake our heads and walk away in confusion. Why would any culture hold in its annals such a themes only to have it re-appear in story after story.

It’s well to remember that in the Middle Ages, fairy stories were prevalent and this continued for centuries…

As mentioned, we’re referring to societies with high infant mortality rates and child sicknesses. Women often reared large families.

For a mother, the idea that her child was “taken” and not “gone” was the central emotional tool that the idea of a changeling offered. Since the fairies would have loved the child they had “taken,” it was likely they would remain forever childlike and in a land of enchantment. The child that had gotten sick and died, on some level, was not the child the mother had given birth to, and therefore the ability for child care and some detachment to provide emotional relief to the mother, albeit in the form of nothing more than a superstition, was often pivotal to recovery from the unthinking - the sickness and death of a child…

I would never wish to give the impression that our Irish ancestors were walking around with this as a core belief system. I’m thinking of those times in life that are often unspoken, when something simple feels like a word of comfort from the departed, hearing a significant song at the right moment, seeing a symbol, a bird… These comforts do not reside in that part of the psyche that encompasses the everyday, but it does offer comfort to that part of us that needs to go on…

The country was deeply Christian for much of its history and a concurrent devotion to the Mother (Mary) and saints, such as St. Brigid (with her attendant earthy folkloric aspects) would have been likely. In fact the devotion to both these women was deepened by their personal narratives of child loss, care and the other relatable aspects of their own experience. While a woman was likely to attend Church by day and pray for her child, it was in the middle of the night, when the depths of loss surfaced and during those inconsolable moments that a woman might draw on the emotional, albeit irrational comfort of her child being elsewhere and happy, with a chance of return, as opposed to the idea that the child was gone forever. And even though belief in an afterlife was ingrained in Irish culture, for a grieving mother, when logic has flown out the window and the heart is sore, this cultural oddity, “the changeling” could provide comfort to some part of a psyche and heart that could find no comfort in either logic, religion or loved ones. As Yeats said, there are some things that are too big “for even the biggest heart to hold.”

“AWAY WITH THE FAIRIES”

What Are they talking about?

Another one! As the sombrero is to Mexico, so goes the Irish - “away with the fairies.“ For the Irish, it can feel like a caricature. But! Yes, I’ve said it before, beneath the surface superstition, the concept of being “away with the fairies” when brought into the light of day illustrates the use of fairy lore as a social tool for reincorporation the disenfranchised or absent back to society, with their dignity intact. What do I mean by that? Well, the best example might be around a bout of depression or other passages that a body might want to leave behind. It’s worth considering how small communities and villages dealt with mental illness or even intermittent depression, in a country that’s not known for its sunlight… If a community member had a ‘bout,” it was easier to put behind them with a general consensus that they had been “away with the fairies.” This social agreement of sorts served to give permission to its most vulnerable to re-enter the daily functioning and communal pursuits of the locality. It negated the necessity for explanation or probing while allowing people to resume social interaction without question or comment. It was a way to “save face.” Any explanation is better than none. And explanations for odd behavior, mental illness and depression weren’t available to people. In truth, mental illness seem to change over time and we still find much of that area, inexplicable and difficult to understand. It’s little wonder that an explanation through the use of fairy lore surfaced…

Here again, the changeling idea is often unearthed. The idea that an adult could be “taken” and therefore not “be themselves” was not that unusual and to some degree continues on a subconscious level. (“I wasn’t myself” of “he wasn’t himself” is a phrase I’ve often heard during my lifetime) And when I think about it, it seems like issues of depression and other mental health diseases (they seem to change over time), can feel to the sufferer as though they are being “taken over” by something over which they have no control. In any event, this mechanism of permission to return to everyday life after difficulty has that sound kindness and wisdom that I’ve come to associate with Irish folkloric tradition.

MYTH, FAIRYLORE AND CARL JUNG

So now that we’ve taken a look at how fairy lore and fairy tales were utilized in society (Middle Ages stories were mostly fairy stories! And it continued for centuries especially in Western Europe) what is it that fairy lore represents? Where does it come from? Similarly mythology would seem to fulfill a similar function in connecting us to the various aspects of human nature. By creating stories around archetypal characters, we see in them extreme versions of our own human quality traits and are thus enabled to detach from clinging to our own small story and to see the world in broader terms, as well as our role in the bigger picture.

Carl Jung often drew upon these so-called archetypal characters of fairy lore and myth as a way of reflecting the psyche. Mythologist Joseph Campbell carried on this work and saw myth as the reflection itself of the human psyche. Combined with symbology and ritual, he regarded the old stories as a key to understanding ourselves and the collective experience of what it means to be human.

“Presence is holding love without twisting it to your desire” Marion Woodman

A list of Jungians including Clarissa Pinkola Estés and Marion Woodman followed suit in drawing deeply from the well of fairy tales as a means of exploring and understand even more aspects of the human psyche.

Did the Irish see it this way? It’s hard to know. In the same way that attendees of Star Wars movies love the stories, are They thinking about the archtypal characters and the story as a reflection of the collective human experience?

FAIRY TALES, MYTH AND STORYTELLING IN HOLLYWOOD

It’s interesting to note that George Lucas drew on much of Joseph Campbell’s studies of the “hero” archetype for his Star Wars movies and openly credits Campbell at every opportunity. “The Power of Myth,” a series of interviews of Campbell by Bill Moyers - and one of PBS most popular shows - actually took place at Lucas’ ranch.

For a time in Hollywood, the Truby method gave classes in the Heroes’ journey, in which seven points are hit on in the profession of the journey the hero is making.

Hollywood stories used to run on the Shakespeare Five-Act structure - sometimes down to the page i.e. specific things had to “happen” by page “x.” It also had a three-act structure, although no one could tell you where on began and another ended. Campbell’s model (as taught in LA by Truby) offered an alternative. Many movies and stories about heroes that do incorporate the seven points as listed by Campbell, did become very successful. The more obvious was the Star Wars movies, which are, for many, a modern form of mythology set in the future, instead of the past. So, lest anyone think mythology or fairy lore are things of the past, check out the “hero” movies and fairy stories (Disney) at your megaplex and it will become clear that humanity has never ceased to cherish fairy lore and mythology. There have, however been some format changes! It’s its own nourishment…

FAIRYTALES CARRIED ON

Marion Woodman

And so many Jungian psychologies continued on in the tradition of Jung and Campbell. For them the stories provided a mirror to the psyche. Clarissa Pinkola Estés surprise success with her “Women Who Run With the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype” evidences the deep interest in stories that resonate and are simply another form of fairytales and myths.

One of my favorite Jungian psychologists is Marion Woodman. It took a while for me to understand her vernacular but once the meaning of the terms became clear, her work held great insights. I am grateful for all her insights, particularly with respect to artists and the creative process and what’s important to transmit to audiences…

Marion defines feminine and masculine in archetypal terms, the idea that we all have masculine and feminine aspects, irrespective of gender. She explains the focus of those tales that address the “conjuncto” or sacred marriage of the self to the self in unifying and balancing all of the self. The masculine (paraphrasing) represents more linear thinking and is more linear in nature. The feminine is more representative of circular thinking and is circular in nature. Honestly, it goes a lot deeper than than but hopefully it gives enough basis to explain a fairytale in this light…

SLEEPING BEAUTY

What does it mean?

In this light, another reading of such tales as “Sleeping Beauty” reveals an entirely new and different meaning e.g. Sleeping Beauty represents the feminine in all of us, and in this case, the part of the feminine that is sleeping and awaits the journey of the Prince (the masculine aspect) through the “forest” to the castle (the castle almost always represents the psyche), often using a sword (discernment) to “cut away” those things that get in the way of his moving forward toward the castle to meet and marry that part of himself, or subconscious, that is “sleeping.”

We often seek in modern times to explain what all the symbolism means but the thinking is that irrespectively of whether we consciously understand the symbols, the effect of hearing these tales is similar. It feeds parts of us.

GREAT LITERATURE AND ARCHTYPES

There is school of thought that relegates the great classic stories of out times to an integration of two aspects of ourselves, namely the conscious and the subconscious, the masculine and feminine. I don’t want to get too deep into the psychology here;) But I found this fascinating anything that helps me to see the world, or stories of the world in a slightly different way, I love to pass it along.

So, when I look at a timeless novel such as “Withering Heights,” which was been described as the ultimate arthtypal story. Heathcliff represents the masculine, a man unable to temper his character. Katherine is similarly lacking. All wildness and raw. Over time and through experience, they “give birth” to the next generation or in archtypal terms, they give birth to a more conscious version of themselves. Their “children” are able to meet each other more easily and ultimately “marry” in a way that the early archtypal versions of the characters could never hope to since they represented the unrefined traits of the feminine and masculine. Once these were tempered, it was easier for the more refined versions of themselves to connect.

When I began to apply this type of symbolic thinking to all the great novels, it opened up a new world for me. In politics, I even find it helpful to view world events as a series of symbolic stories and much as with fairy lore, fairy tales and myth, it gives me a different view and helps to put things in perspective.

I never stop learning from these stories and songs that were all left to us and for us… Whatever has happened or will happen to me is likely to have happened to those who have gone before - at least at a symbolic level - and knowing this, hearing the stories, hearing the songs, learning them, singing them and thinking about them helps me to be in the world because as much as it appears to be changing, what it means to be human remains very much - the same…

WHY DID FAIRYTALES DIE OUT? DISNEY…

Carl Jung and his cohorts came on the scene parallel to the dying out of fairy lore and many of the folkloric traditions I write about on this site.

By the mid-twentieth Century, Ireland was quickly moving from a country of mostly small farmers into a newer age. Immigration was high (and always had been), but combine outside influences, with a new availability of newspapers and the advent of mass-transportation, fairy lore and many of its attendant traditions went out of fashion. And not for the first time.

Interestingly electric was also a factor in the demise of the practice of fairy story telling. It was easier to belief in the presence of the unknown prior to electric light. And if you’ve ever walked a country road on a dark night with no sign of a moon for guidance, it’s easy to see where the idea of fairies come from. More accurately, we ascribe our “fears” to the dark but ultimately, the deepest fear is what’s in ourselves.

So, when light came to houses and villages and it was possible to “see in the dark,” something in us stopped looking for it outside the door and began to look within.

The advent of newspapers made it more difficult to suspend belief in the existing fairy lore structures as a means of dealing with our human nature. So began the reading of “real” stories from around the world. In addition, immigrants who could now return due to mass transportation carried a new sensibility that didn’t always embrace the old stories or ways.

And so, it would appear to make perfect sense that the seeds of archetypal psychology came to sprout within a short time of the introduction of electricity, mass transportation and media. Soon the world gave us Jung.

IRISH FAIRYLORE AND THE DARK HALF OF THE YEAR

I really enjoy the Celtic cycle of the year and have recorded a lot around it, probably mostly because I love the idea of the outer and inner life reflecting each other and having traditions and ways of marking them. From an Irish perspectively, I don’t think I’m alone in this.

As I’ve written extensively, in the old cycle of the year, day began at dusk, not dawn since the dark was always thought to come before the light, much as with childbirth.

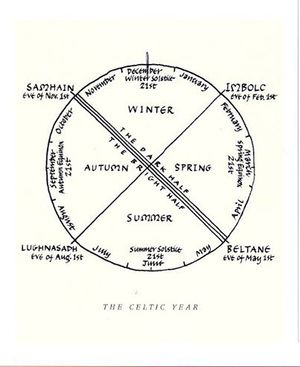

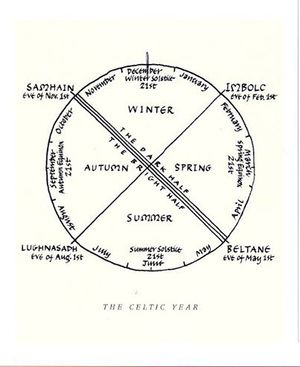

And the year was divided into two halves, the light half and the dark half. New Year’s Eve began at dawn on the feast of Samhain (Oct 31st) and went until May Day. The light half began on May Day and run until Samhain. The year was divided into “quarter days” or “pattern days” as they later came to be known. The two other pattern days were Lughnasadh (August 1) and Imbolc (Feb 1). The solstices and equinoxes were also acknowledged.

The light half of the year consisted of the business of life, our business. It was the time to sew crops, and harvest them. It was the time for activities of all kinds and very importantly, it was the time of marriages. The light half belonged to the people.

The dark half was believed to belong to the otherworld.

It’s when we begin to view this otherworld, not as a series of fantastical characters, but as a reflection of our inner nature, that we can come to enjoy the richness of fairy tales and the valuable function they serve.

So, it might be fairer to say the light half is for our active selves, the external half. And the dark half is for contemplation, the inner self.

WHAT OTHERWORLD?

There are, broadly speaking, three otherworlds that are often referenced in Irish fairy stories and writings. And I do mean broadly since it’s a multi-faceted area.

The Land Beneath the Waves.

Seafaring men (and they were virtually all male) of old viewed the land beneath the waves as a mysterious netherworld of sorts. Irish mythology and even its songs refers to mermaids.

There’s a plethora of songs about Selkies, another type of sea creature related to the seal that transforms into human formon land, usually, tho not always in female form.